India’s energy storage story

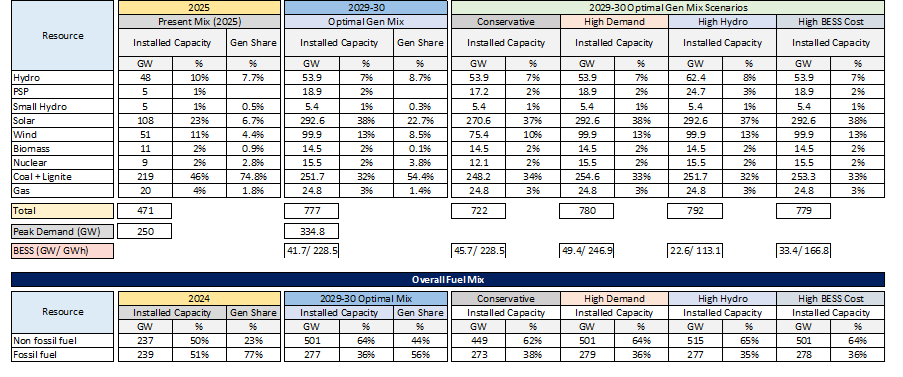

As of May 2025, India’s power capacity stands at 50% thermal (coal + gas), 47.3% renewable energy (wind, solar, hydro, biomass combined) and 2% through nuclear. But if we convert this metric to electricity, India is still powered by 75% coal, 13% through wind and solar and 8% through hydro.

Through an installed capacity of 108GW of Solar, 51GW of Wind and 48GW of hydro, India manages only 22% of its electricity supply through renewable sources (hydro included).

The Central Electricity Authority, through its National Electricity Plan document, estimates that if India is to achieve its COP 26 goals, it will need 292GW of solar, 100GW of wind, accompanied by 41.7GW/228.5GWh of battery storage capacity along with 18GW of pumped hydro, ranging between 6-8 hours of storage.

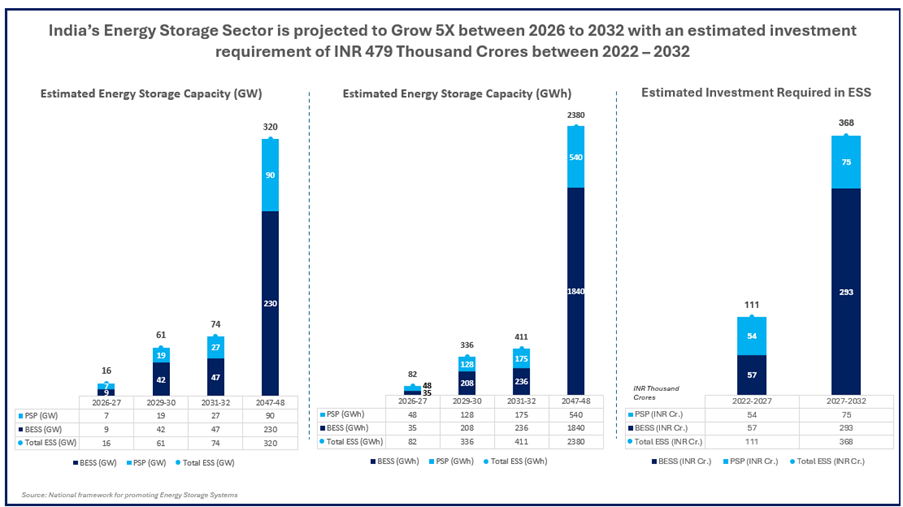

In doing so, India will achieve a generation share of renewables that rises to 44% while that of fossil fuel energy (coal + gas + nuclear) will be 56%. India will require a total investment of US$55 billion between 2022 and 2032 to realise the same for energy storage systems (ESS, including BESS and pumped hydro).

This, from an installed base of 500MWh of BESS and 4.8GW of PSP. i.e. almost nothing!

India has acknowledged the need to ramp up energy storage fast, with multiple policy and regulatory enablers. As a measure to accelerate demand, India has introduced (1) Energy Storage Obligation (ESO). It aims to facilitate renewable energy deployment by enhancing grid stability and managing the variability of solar and wind power.

India’s ESO targets are set to increase from 1% in the financial year (FY) 2023-24 to 4% by FY 2029-30, with an annual increase of 0.5%. In addition, India introduced an advisory that (2) all new solar installations in the country have to be coupled with 10% ESS (2-hour duration). This is expected to increase in the coming years; the advisory also includes rooftop solar.

The government has also introduced a (3) Viability Gap Funding (VGF) scheme to support standalone BESS projects of a total capacity of 13.5GWh, for which the Government will fund 30% of the project CAPEX, payable at tranches of construction and operation. A second phase of the VGF support has just been announced today by the Ministry of Power (MoP) too, to support an additional 30GWh of projects with 16% support on CAPEX. The support has also been extended to 15 states and major power producer NTPC to integrate BESS with their existing thermal fleet to better utilise the plants.

India’s government has, over time, defined (4) standard bidding guidelines for such projects and (5) created a framework for ESS projects and developed (5) a separate policy for PSP development, along with talks of introducing VGF for PSP development too.

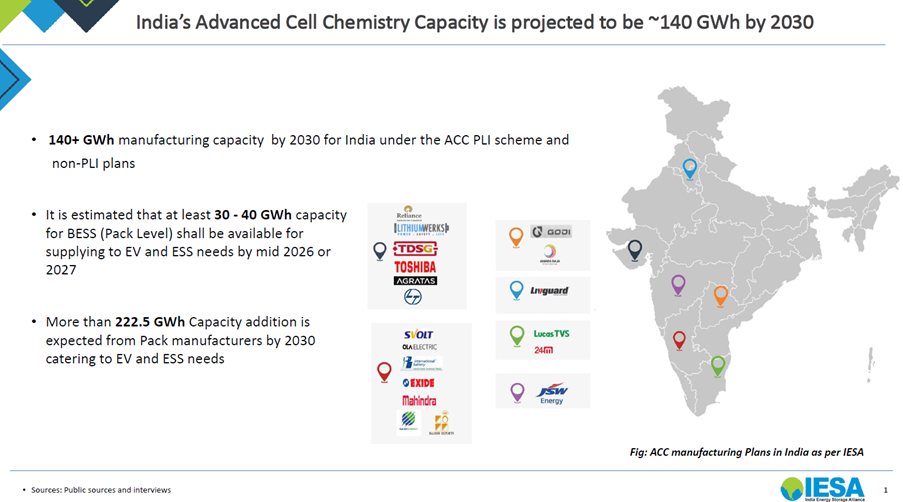

India has well understood that only accelerating demand would still make the country dependant for resources from other countries; to further focus on ‘Make in India,’ the government introduced a Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for US$2.1 billion to domestically manufacture 50GWh of Advanced Cell Chemistry (ACC) batteries in the country, paid on demonstration of 65% value creation within the country in phases.

As of today, 40GWh has been successfully awarded, and 10GWh is pending to be awarded.

India formed a critical mineral mission, identified 30 critical raw minerals for the country, and is looking out for partnerships with countries to tie up for processing/ refining these raw minerals. Multiple tax exemptions have been introduced, and Basic Customs Duties (BCD) have been implemented to encourage players to make in India and not import from outside.

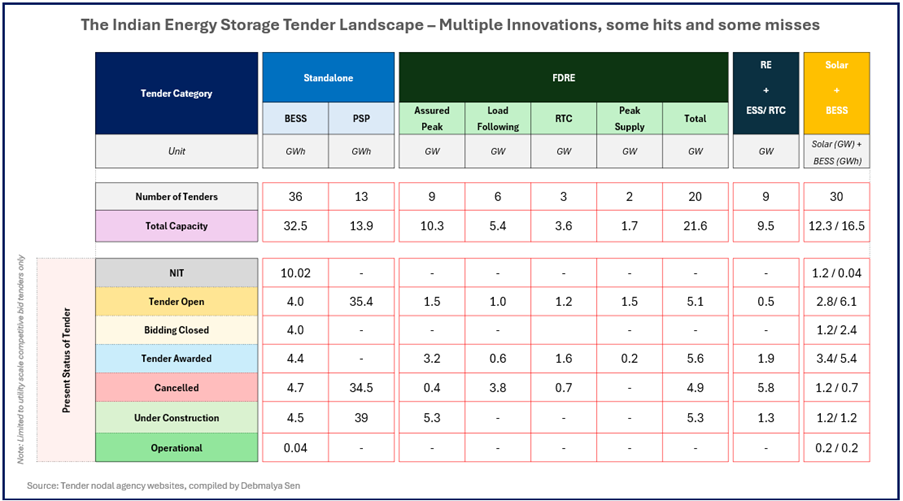

ESS installations in India are driven by tenders floated by central government identified agencies called nodal agencies, and states, too. The identified central nodal agencies act as intermediary bodies, derisking the power procurement process and payment mechanism.

The central nodal agencies are namely SECI, NTPC, NHPC and SJVN. Along with the same, India’s states have also come forward in sharing ESS tenders, namely Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu. Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Odisa.

The tenders in India are broadly of 3 types

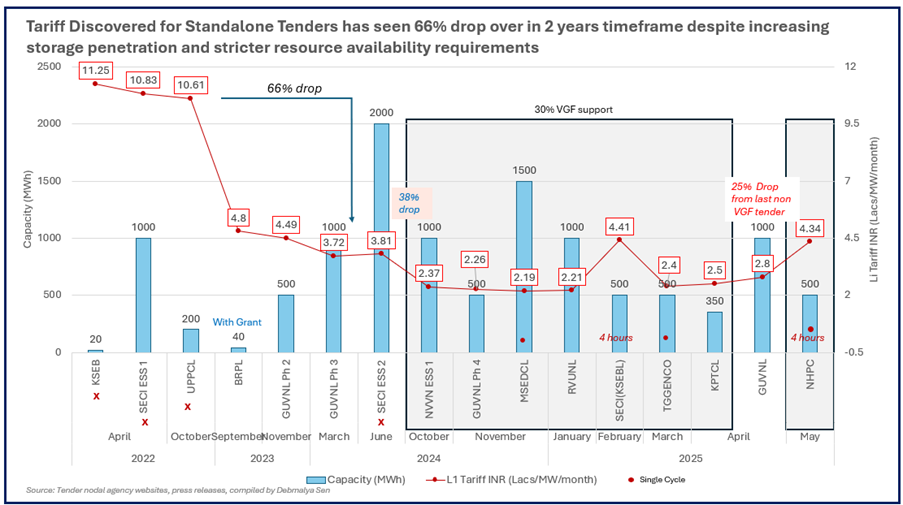

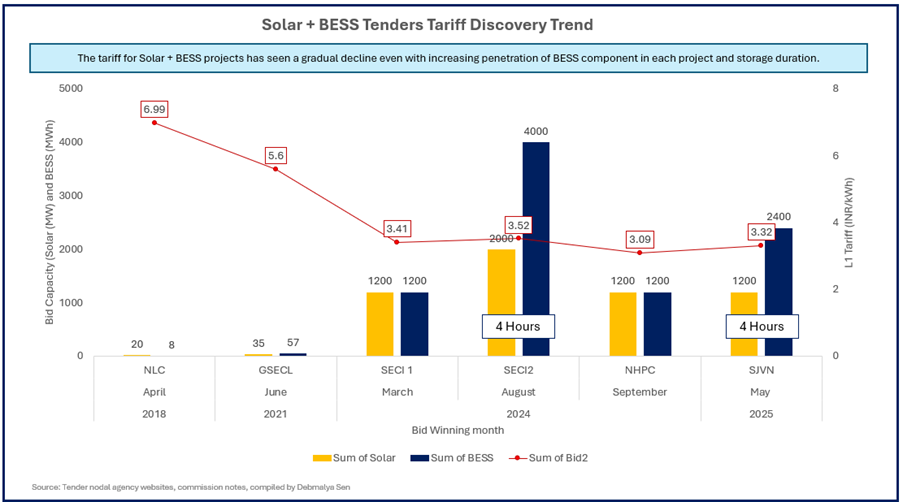

- Standalone BESS/ PSP tenders: where for a tenor of 12-15 years (40 years for PSP) a developer must build-own-operate (BOO) a BESS/ PSP project (often build-own-operate-transfer, or BOOT, for PSP), off-taker is often defined in such tenders, and the bidder has to quote capacity charge value to bid (INR/MW/month or INR/MWh/year). The charging power to charge the BESS or pump water in the reservoir is given by the procurer free of charge. Generally, the tenders require 2-cycle operation for 2 hours for BESS with allowed degradation of 2.5% annually, whereas for PSP the discharge duration is typically 5 hours continuous, with the requirement to pump for 8 hours. The reverse auction system is followed for all tenders to select the winner of the tender, who is thus awarded the project and must commission it in 18 months (five years for PSP). These tenders are further assisted by VGF of 30% on CAPEX by the government, which further makes them attractive and more attractive for multiple players to bid for. The graph below shows the success of such tenders from the pre-VGF era to the post-VGF era, where a price drop of 66% have been seen over two years to a further drop of 38% through the introduction of VGF.

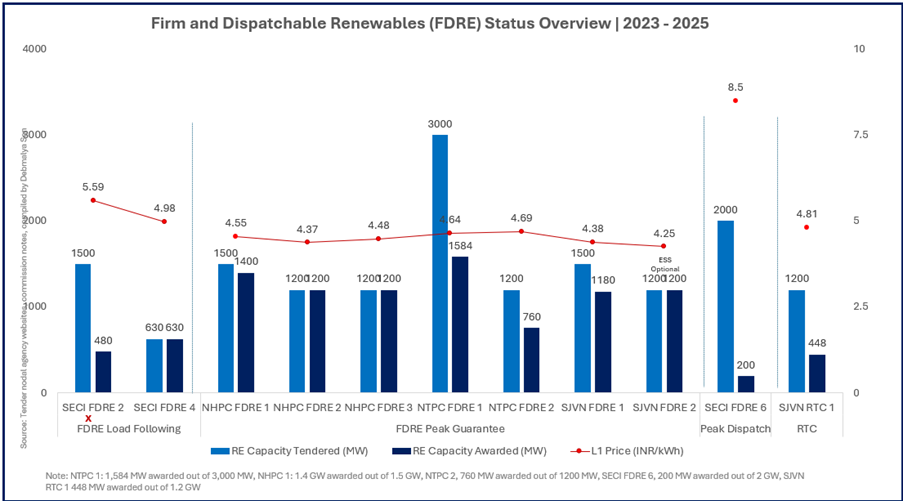

- Firm and Dispatchable Renewable Energy (FDRE) tenders: These tenders are basically Solar + Wind + ESS tenders with some specific requirements. The concept came from making renewables firm and dispatchable. FDRE is of four types:

(a) Assured peak model – in such a tender off-taker will take whatever power the developer gives through out the day, in peak hours (identified and communicated to the developer on a day ahead basis), for 4 hours the developer needs to dispatch at 90% of installed capacity basis, the annual CUF defined in such tenders is 40% and the quoted bid is INR/kWh basis. ESS is mandatory generally defined as 0.25kWh per MW of RE. This category of FDRE has seen the maximum tenders and success too.

(b) The second variant is the Load-Following Model – wherein a load profile is shared in the tender and the developer needs to meet that load profile with a metric of 75-90% Demand Fulfilment Ratio (DFR), the quoted tariff is INR/kWh. As one would expect, this variant has not seen success in any of the tenders.

(c) The third variant is Round the Clock (RTC) tenders, here ESS is optional, the developer needs to install RE with a defined availability of 80% monthly and 90% during peak hours every day. This has been moderately successful.

(d) The fourth variant is (4) peak-specific model, which is a solar + BESS tender with only dispatch required during peak hours (4 hours). The bids are submitted in INR/kWh form.

The below graph shows the tariff discovered and the bid capacity tendered versus that being bid for all the four variants of FDRE. Tariffs ranging between US$ 0.05- 0.06/kWh

- The third variant of tender is solar coupled with BESS tenders. These tenders are of a 25-year power purchase agreement (PPA), build-own-operate (BOO) type, where in the BESS dispatch is required for 2 to 4 hours with a 50% penetration of BESS in MW terms. The annual CUF requirement for such tenders is 19-25% apart from the BESS dispatch hours. This variant has found enough attraction and success in the tendering arena, with tariff discovery of US$0.035-0.039/kWh, seen for 2 and 4 hours of dispatch designs.

Multiple players have been participating in such bids. With RE players making it more crowded in the FDRE and Solar + BESS space, new players are getting into the standalone space.

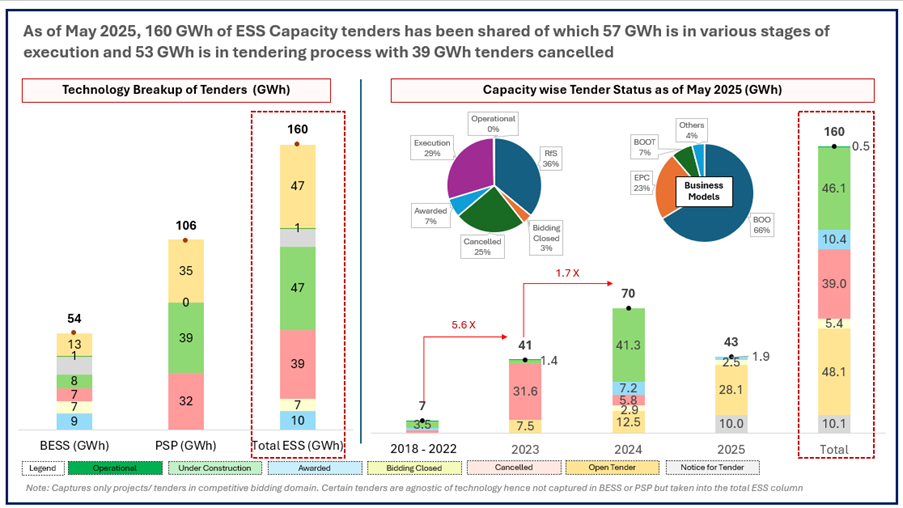

Cumulatively, more than 160GWh of ESS-linked tenders have been issued in India, with 54GWh of BESS and 106GWh of PSP tenders. Around 57GWh is in various stages of execution, and 53GWh is in the active tendering stage. The graph shows the details of the capacity breakup.

India’s manufacturing space has not been that eventful. While 40GWh of PLI scheme support has been awarded to Reliance, OLA and Rajesh Exports, the commissioning of the same has faced delays.

It is expected that by 2030, India will have 140+GWh of battery manufacturing capacity, based on announcements made. The pack manufacturing space has been quite promising, with the expectation of 225GWh of pack manufacturing capacity in India by the end of this decade. The demand anyway supersedes the supply, as per analysis by Customized Energy Solutions, the expected demand both from EV and ESS is expected to be around 2TWh by 2031-32.

There are emerging talks of looking into ways of increasing domestication through introducing an Approved list of Battery Manufacturers in India and increased Customs Duty on the importation of containerised solutions in India, as the thought is that India can domesticate the container much earlier.

Overall, India has been taking the right measures both on accelerating demand and securing supply to meet its COP26 commitment, where energy storage is going to play a critical role. To nurture the same with careful hands is exactly what India is doing. Of course not every move is perfect; there is scope for improvement, but India is prepping up to be the third-largest country in terms of battery demand by 2030 (IEA).

At the 11th India Energy Storage Week (IESW), happening in Delhi from 8-10 July, India joins in to celebrate the success stories seen in India and discuss how to cater to this growing demand.

Debmalya Sen is the president of India Energy Storage Alliance (IESA), where he leads an alliance of 180+ members across the value chain, helping them in their journey to accelerate energy storage deployment. He works closely with the government and private sector to give key recommendations on energy storage and is also a recognised subject matter expert in energy storage by the Central Electricity Authority. Before joining IESA, Debmalya was the India Lead of the World Economic Forum, and a management consultant in KPMG, where he led advisory work on energy storage and renewables. Debmalya is also a mentor selected by ESMAP (World Bank) for energy storage, and he mentors young women engineers interested in pursuing a career in the energy storage domain.

energy-storage